When the notable men of the Midland Railway decided to bring their service into London, none of them could have foreseen the problems that were to beset them, but in the great age of steam the Victorians seemed to thrive on solving problems.

In 1844, as president of the Board of Trade, William Gladstone introduced the Railway bill. As a result of this bill, railway companies were compelled to introduce ‘Parliamentary Trains’. These trains had to carry third class passengers for fares not exceeding one penny per mile.

They had to stop at every station and travel at not less than twelve miles per hour.

On most railways these carriages were called ‘Government Class’. This was the year that the Midland Railway was formed by act of parliament from three existing railway companies: The North Midland, the Midland Counties and the Birmingham and Derby Junction.

The first General Meeting of the shareholders of the newly formed Midland Railway Company was held in Derby on Tuesday the 16th of July that year. The meeting was presided over by the chairman of the board of directors, Mr George Hudson. It was such a well-attended meeting it was held in the large engine shed opposite Derby station.

At the time of the first Great Exhibition in London in 1851, the Midland Railway was using the tracks of the London and North Western Railway to travel south of their Station at Rugby. Later on, they started to use the tracks of the Great Northern Railway into Kings Cross. They were able to 'stable' their trains outside the station and they purchased land here to use for goods traffic.

During busy periods they lost a lot of passenger traffic to The Great Northern as they were given less track time and also less stabling facilities in Kings Cross.

The first obstacle was getting government approval for the plan to extend the Midland railway line into London and build a new terminus, and this needed an act of parliament which took twelve years to secure – the act was passed on the 22nd of June 1863 and work began to purchase and clear the lands necessary to achieve the project.

The site was chosen because this was the nearest central point the railway could reach in London from a northern approach; an act of parliament was passed when the second station, Euston, was built in 1836, forbidding the railways from passing over Euston road, after the gentlemen of the City of London expressed their concerns at the prospect of the city being overrun by the lower classes travelling in from the Midlands and the fear of another fire of London being caused by the coke boilers of the steam locomotives.

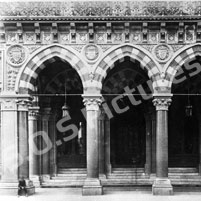

The consultant engineer to the Midland Railway Company, William Henry Barlow, was to design the largest single-span roof in the world to cover the new St. Pancras Terminus to herald the arrival of their trains.

Barlow had previously been chief engineer of the company from 1842 to 1857. His principle assistant was Mr Campion, who in turn had an assistant, Mr Grier. (Builder 09/04/1870).

Unlike the Great Northern Railway Company at Kings Cross, Barlow had decided to bring the track over the Regents canal.

There had been many problems with the close proximity that the canal presented to the lines exiting Kings Cross station, not least the slow journey down into the tunnel and the subsequent steep haul up the northern side; this had to be aided by teams of horses when the slippery conditions on the rails called for it.

By carrying his lines in above street level, Barlow was also able to make the best of the very narrow clearance between the gas holders of the largest gas works in Europe, The Imperial Gas Light & Coke Company, which were to the east, and the graveyard of old St. Pancras churchyard on the west, although work to widen this route by moving graves further west was still necessary.

As the Midland route going north was longer than those of their rivals, any time that could be saved was paramount. This meant that the train shed would be elevated above street level. Here he had the option to build the terminus on a man-made hill, an easy choice, with the spoil from the recently constructed Metropolitan underground tunnels available, or to create a lower level which could therefore provide space for storage. With the Burton & Trent Brewery keen to use this space for storage of their beer he chose the latter option and the deck for the track stood on 705 cast-iron columns: 47 column rows north to south, 15 column rows east to west.

(Initially shown as 690 columns in the archive of the 20th of November 1867) (min644). The columns are placed at 14ft 9inch centres.

Each column stands on a substantial brickwork base. The columns were tied together using 1,905 cross-girders and then a deck was formed from 9,012 buckle plates, riveted in place.

Above this, small brick arches were formed to bring up the height of the timber platforms laid on top. The reason for using a single span roof was so the platforms could be moved to suit whatever gauge of track or tracks was eventually to go from the terminus – Isambard Kingdom Brunel had introduced the 7ft gauge of track on his Great Western Railway, whereas the other early railways of Britain mainly used a 4ft 8½ inch gauge.

Although Brunel's arguably favourable gauge was not adopted by any of the other British companies, the idea was still in the ether and wasn't finally abandoned by the Great Western until 1892.

If the larger track gauge was adopted, the single span allowed the most freedom to move the platforms. There were several other problems to solve; the large gas holders in Battlebridge road forced the tracks over to the west, which then encroached upon the graveyard at St. Pancras old church.

Graves would have to be moved. Waring Brothers were paid 'on account of removing bodies £3,762, 16s and 5d. But gravediggers had to be brought in to carry out the work, because the labourers were unable to deal with the putrefying mess including cholera victims that they were faced with.

Indeed, they were blamed for a subsequent cholera outbreak. Archibald Campbell Tait, Bishop of London, appointed Arthur Blomfield, son of his predecessor and with a rising reputation as an architect, to supervise the execution of the task.

Blomfield was most concerned that the gravediggers might be less than irreverent in completing the task, by not burying the correctly identified and complete corpses in the correct manner. He engaged a clerk of works to attend the site regularly and at all times during the removal of bodies to ensure that the job was carried out dutifully.

To keep the clerk of works on his guard Blomfield appointed one of his own young assistants to call in irregularly, without warning.

This young man's name was Thomas Hardy. Hardy is the first of many 'literary greats' that you will find connected to this building and mentioned by me. Blomfield himself would also arrive from time to time without notice.

Until 1825 the Fleet River openly flowed along the line of Pancras Road.

The river was so reduced in size by this time (approximately six feet wide and one foot deep), that it was able to be encased in an iron tube and placed below the road level.

The course of the river takes it under Euston Road down to Holborn and it flows into the River Thames through a grating under Blackfriars Bridge.

Rowland Mason Ordish (1824-1886), an engineer, helped Barlow's design for the roof actually work, and also supplied designs for other ironwork details in the station, including the framework for the 18ft (5.48m) clock.

Ordish had worked on the Crystal palace at Hyde Park in a minor capacity on the iron and glass roof of the designer and Midland Railway director, Sir Joseph Paxton.

He also designed a rather less successful structure, Albert Bridge over the Thames. Perhaps fortunately for Ordish, funds for this structure were not available until after he had been involved with St. Pancras, as the bridge, which opened in 1871, was structurally poor and had to be reinforced only 10 years later – remedial work was carried out by Joseph Bazalgette.

Ordish went on to design the roof of the Royal Albert Hall and then to copy St. Pancras up in Glasgow for the roof of St. Enoch Station.

In 1865, the work on the station began. Waring Brothers were awarded the contract to build the foundations and brick-arch basements, as well as the goods station and approach walls, and this carried on through to the sections under the hotel.

They were overseen by Mr Grier. Waring Bros specialised in building railways across the world and were also involved in the cut and cover construction of the Metropolitan Railway, the first underground railway system.

The Metropolitan line was to run under the front of the hotel site, passing beneath the Porte- cochere which has extra-large beams under the ground level to support the weight of the hotel.

But although the tunnel was built, it went unused until 1920 when it was incorporated into the Circle line. The Midland Railway trains were able to run on to the Metropolitan line tracks by way of a branch tunnel under the Western side of the site.

The original plan had proposed that Midland traffic would be able to join the Metropolitan line and travel both east and west at their junction, but after objections, the line eventually only travelled east.

This tunnel now forms part of the Thameslink (First Capital Connect) service and the modern station was built around it during the CTRL works of 2001-2007. Appleby Brothers provided the original hoisting machinery.

Charles Casebourne of Hartlepool supplied the lime mortars used in the station and hotel.

Bricks to form the substantial foundations were made on site.

The wrought-iron beams of the shed roof were supplied by The Butterly Company of Derby, under the management of Mr (later Sir) G.J.N Alleyne.

The foreman of the works at St. Pancras was Mr Clark. There are 25 principle ribs in the roof, weighing about 50 tons and costing £1000 each.

On May the 3rd 1865 a competition was launched by the Midland Railway to find an architect to design the hotel, which was to include office space for the Midland Railway Company headquarters.

The Midland Railway Company were the only large railway not to have a headquarters in London, theirs being in Derby.

Ten architects were invited to enter the competition, but after the entry period was extended to accommodate Scott and others, there were Thirteen:

It was awarded to George Gilbert Scott in January 1866, after the extension period of one month was added to the entry date. The runners-up were G. Somers Clarke, E.M. Barry and T.C. Sorby.

George Gilbert Scott, 13th July 1811 - 27th March 1878, was born in Gawcott, a small village near Buckingham.

The Fourth son of the Reverend Thomas Scott and Euphemia Lynch, Grandson of the Biblical commentator, Thomas Scott, he was initially educated in the church school which his father ran to increase his income.

In 1827 he travelled to Homerton in East London to study as an architect under James Edmeston, an architect and hymn writer.

After almost six years with Edmeston, Scott assisted Henry Roberts and occasionally his friend Sampson Kempthorne. In 1835 Scott himself employed an assistant, William Bonython Moffatt.

Three years later in 1838 Scott became business partners with Moffatt and marital partner of his childhood sweetheart, Caroline Oldrid, also his first cousin.

Scott & Moffatt completed over 40 workhouses and many churches over the following 10 years. Although Moffatt was good at securing work, it would seem that earnings were often low or non-existent.

At the insistence of his wife Caroline, Scott ended the partnership. A more profitable career ensued.

When Scott's design for The Midland Grand Hotel was chosen he was one of the most eminent architects at that time and certainly one of the best known publicly, after all the trouble he had with his designs for the Foreign office.

He was a late entrant for the competition for the hotel, following the recommendation of a friend, Josiah Lewis, a member of the board of directors of the Midland Railway Company.

Lewis had recognised that this was at last an opportunity for Scott to complete a secular building in his preferred gothic revival style in London.

After persuading the rest of the board to extend the deadline for competition entries, he then had to persuade Scott to enter.

Scott had originally designed the Foreign office in this, his favoured style, winning the competition in 1858 under short-time Prime Minister the Earl of Derby, only to have these accepted designs rebuked by Lord Palmerston when he became Prime Minister after the competition, but before the work had started.

Palmerston insisted that Scott redesign the offices in the classical style or withdraw and allow someone else to complete them. Palmerston had another architect: Henry Garling, in mind.

Scott chose the former, presenting his classical style to Palmerston's committee and they agreed to the changes being built – something Palmerston could not easily change. When the building was finished neither man liked the result.

There were also complaints from the staff occupying the new offices of the lack of good heating and ventilation arrangements but the buildings still fulfil the needs today.

The original drawings for the hotel at St. Pancras were completed in a small hotel during a three-week period in September and October 1865, whilst Scott accompanied his wife, Carolyn on a trip to Hayling, near Portsmouth, to nurse 16 year old Alwyne Gilbert, their fourth son.

Alwyne was serving in the Royal navy and was suffering from scurvy.

Always quite delicate, he died thirteen years later at the very early age of 29 – it was 1878, the same year that Sir George died.

When Scott was announced winner of the competition and his plans shown, some of the other entrants bemoaned the fact that, if they too had been allowed to work outside the parameters laid down by the Midland Railway, they could have done a better job.

Indeed, Scott's estimate for his plan was £50,000 more than his nearest rival and his design some two storeys higher than specified.

Nevertheless, the appointment was made and Scott brought in immediately to oversee building works and confer with Barlow on accommodation needed for the railway.

This accommodation would occupy the side buildings of the station and included toilets, booking hall, ticket office, lamp room, waiting rooms, Staff rooms, offices etc.

Then, the first of many financial problems occurred; the Overend and Gurney bank collapsed in June 1866, (the largest bank crash in British history until 1995).

This caused the Directors of the Midland railway to revise their plans at St. Pancras. Firstly, they decided not to move their headquarters to London.

Secondly, they told Scott that he must change his design to save a considerable amount on the estimated cost.

Scott removed the entire fourth floor of accommodation from the designs for an estimated saving of £20,000.

Additional savings were to be made "wherever it was practicable to do so". The plans were redrawn and along with the removal of one entire floor, the central tower and clock tower were altered to be more equal in height.

The rooms originally set aside for the Headquarters were re-configured into bedrooms.

Scott was invited to a meeting of the Midland board in December 1866 to show his revised drawings and estimates of costs.

John Saville was appointed the Clerk of works on January the 1st 1867, bringing in his own son to assist him. They got underway with the foundations of the hotel, which were nearly finished when the Station opened to passenger traffic on October the first 1868.

It is important to realize that although the station was open, it was by no means completed and a letter to the board of directors from William Barlow dated April the 5th 1869 states: 'The platforms and cab stand adjoining the main offices at the South end of the station are now being proceeded with and will be completed in the course of the present month'. (min 1144).

The side walls of the train shed had also still to be completed. Lucas Brothers (Builders of the Royal Albert Hall, Royal Opera House, Kings College Hospital, Alexandra Palace, Woolwich Arsenal, Etc.,) worked on the Eastern cab road and platforms.

Noted Engineer John Hawkshaw (Later Sir John Hawkshaw) provided some drawings. Scott had encountered problems with the slow rate of the supply of both bricks and stonework, much to the annoyance of the board of directors and the travelling public.

A junior clerk of works was despatched to the stone quarry to discover what was causing the delay and to remain there until all the stone was supplied.

The walls were finished in early 1869 and Scott was able to go ahead with the Hotel above ground level.

Work got underway at the south-east corner of the site, on Pancras road. The basement and ground floor were almost completed as part of the station works.

Waring Brothers were also paid for 'attending on gas, fittings, etc, as per Mr Kirtley in the Booking Office'. They finished their contract by the first of May 1869 (minute 1157).

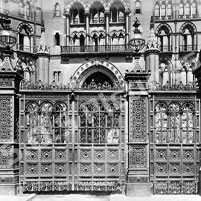

Mathew Kirtley (1813-1873) was Locomotive Superintendent for the MRC, designing early Locomotives and buffers. The booking office was the first building completed by Scott and had a magnificent hipped glass and timber lantern roof.

This very gothic-looking building did not sit well, at first, with the rather modern-looking iron and glass shed next to it, and came in for much criticism from Scott's detractors and rivals.

James Haywood of Phoenix Foundry, Derby tendered and got the work for the Glass & Wrought Iron Cab rank roof at £861, 13 shillings and seven pence.

(Minute 997) Their other famous work in London includes Battersea bridge. In October 1869 he also won the tender for the station clock house at £215 (minute 1217).

The clock itself, some 18ft (5.5m) in diameter, with a face of slate, as with all the clocks in the hotel and in the clock tower, were designed and supplied by John Walker.

The building company awarded the contract for the main construction of the hotel was Jackson & Shaw of Victoria, South-West London.

The building was to use 'Moreland's patented fireproof flooring system', a wrought iron, concrete and corrugated iron 'sandwich' designed to withhold the effects of fire.

Richard Moreland was situated at 3 Old Street EC1.

All tenders received by the Midland Railway Company were decided on the cost, every contract was given to the lowest priced bidder provided they met the stringent criteria laid down by the MRC and could cope with the supply.

The Midland railway made a condition that, where possible, Scott should use materials from the Midlands – this had several benefits: the hotel would be a showcase for Midland materials and craftsmanship, the materials and supplying companies were more likely to be known to the Midland Railway; all the suppliers would use the railway to bring the materials down to London, creating further income for the railway; admirers of the new hotel might choose to use the same materials or furnishings, generating yet more income from their carriage on the railway.

The Facing bricks used in the construction were from Edward Gripper in Nottinghamshire.

Gripper won the tender not on price alone, but on the ability to keep up a constant supply – so when this proved impossible he used George Tucker in Leicestershire.

The approximate cost of these bricks was one guinea, £1.05p, per thousand.

They are a very hard-faced brick, made from a mixture of Kueper-marl (West Mercia mud) and Pleistocene; this was double-fired in a patented 'Hoffman' kiln which had two ovens, the main one directly fired, the secondary one warmed by the main one was used to pre-fire the moulded mixture.

Coupled with an unusually thin (5mm) lime mortar this gave a very hard wearing fascia to the building. The secondary and internal bricks were made on site at St. Pancras.

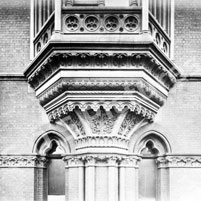

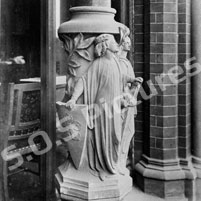

Unfortunately, the stonework was not quite as hard wearing; carved by masons from the company of Farmer and Brindley, there is Sandstone from Ketton, Ancaster, Mansfield and York.

These were more susceptible to contamination and erosion caused by the London atmosphere, although the hotel later publicised the fact that this location was 'Away from the riven fogs'.

The graduated slate roof tiles were originally from the Groby & Swithland quarry, Leicestershire, (since replaced with Westmoreland green slates in 1993-4).

Welsh slate was used in areas that were out of sight, at the rear (northern) side of the roof.

The granite and lime-stone columns are from other parts of the British Isles; there is granite from Shap near Cumbria and Peterhead in Scotland and Limestone from Cornwall.

Alternating Limestone columns of red from Devonshire and green from Connemara adorn the Grand Coffee lounge.

Fibrous plaster ceiling roses, cornices and skirting along with fireplaces, decoration & lighting were again individually selected by Scott, and approved by the board, but I have been unable to find any common thread or pattern in which he made those selections, except for the fact that all the rooms intended for public use had perforated cornices, to allow ventilation through flues incorporated into the walls.

Where there was more than one ceiling rose in a room or corridor, he used alternating designs.

John Oldrid Scott, the second son of George Gilbert was brought in to assist, mainly with decoration.

At the committee meeting on October 5th 1869 the board resolved 'that Mr Scott be written to, to say that before he orders the fittings for the interiors of the Hotel, the committee would be glad to confer with him on the subject'.

(Minute 1222) This was the start of a pattern of objections to Scott's plans of opulence and the board's desire to save money.

Gillows of Lancaster (known as Waring & Gillows after 1897) were appointed furnishers of the building.

The furniture was often bespoke, including fitted hall cupboards and cabinets (by Jackson & Shaw).

Each floor of bedrooms used different timber for the furnishings.

The Royal Porcelain Company of Worcestershire was chosen as provider of crockery.

Peyton & Peyton supplied the beds & bedding, Pegler of Leeds the linen, P.C. Osler the glassware and Elkington the plate. D & E Bailey supplied the hardware.

The door locks were by Charles Smith & Sons of Deritend Bridge works, Birmingham.

The door furniture was mainly designed by Scott.

Each door had its fittings custom selected by Scott depending on the use of the room and each set of fittings were engraved with a number so as to identify the door it was to be fitted to.

On March the 1st 1870 it was reported that the waiting rooms in the station were 'rendered offensive' by smoke coming down the chimney.

It was suggested that Mr. Saville be written to on the matter.

In December 1870 George Gilbert Scott was asked to furnish plans for the fitting out of the kitchens and the laundry; at the meeting of the Southern Construction Committee on the 3rd of January 1871 Mr Saville produced one of £5,765, five shillings and one penny (minute 1326). The matter was referred to the board.

In May 1871 the subject of water supply for both the hotel and the station came up (1351).

The engineer, Mr Crossley, had calculated a need for 80,000 gallons (360,000 litres) of water per day to service both the hotel and the terminus. The local water supply company was the New River Company and they were able to supply this amount at a charge of three pennies per thousand gallons- £1 per day.

This was thought too costly an option, so alternative sources were sought. The Regents Canal Company offered a supply for the purpose of locomotive & carriage cleaning, but they could only cope with supplying 40,000 gallons per day – only half of that which was required and at no better price.

Mr Crossley suggested that the Midland Railway dig an Artesian well for the purpose.

The well was sunk between August and September 1871 (1376). Six-feet in diameter, to a depth of 150ft (45m), the well was lined in 9" brick. A cast iron tube was driven a further 50ft (15m) through the ground until it entered the water table and the well filled to a depth of 30ft (9m).

A steam engine attached to an accumulator in the basement was used to pump the water up to the water tank in the West tower.

(Illustration) Concerned that this steam engine would be noisome, smelly and might even fail and that the provision of a second engine would all but negate the benefits of having their own supply, a standby supply was secured from the New River Company, fitted with a meter, so that, should they need to use it, they would only be charged for the water thus needed.

On December the 5th 1871 the first lift was ordered from Sir William Armstrong. The cost was £1,619. 17s 6d.

This octagonal lift was to run from basement to fifth floor. With the carriage provided with a sliding gate on both the South and North sides, passengers were able to enter from either the station, across a small corridor, or from the Terrace lounge.

They could alight on the first to fifth floors via the South entrance only, as there was a rope-driven luggage lift fitted behind the octagonal shaft at these levels.

In January 1872 Mr Allport produced a plan proposing that steps should be built into the front wall on Pancras Road where they still are today. (1389).

The building work continued from east to west, and the directors of the Midland Railway Company decided that the hotel would open in 1873, before the west wing was constructed.

Unbeknown to Scott, the Directors had already commissioned a study into the feasibility of not building the west wing, but instead finishing the building at the western arch – which had returned a favourable verdict to them.

On the first of May 1872 the Southern Construction committee were divided over a proposal by Mr Heygate and seconded by Mr Hutchinson, that no fresh construction should be undertaken west of the central tower, although this section of the building already occupied the site up to platform level.

The motion was defeated by a majority of nine to four. Scott fought the plan and successfully argued his case for completion.

The West wing was completed up to the height of the rest of the building apart from the section north of the Grand staircase – this was finished at the first-floor level.

Hot water apparatus was mentioned in the minutes of the meeting of April 2nd 1872 (min 1410).

A manager was sought and applications were received in January 1872. Thirty-six applications were opened for consideration, and a shortlist of three was compiled, but there was one late applicant that the board decided to interview, received on February 6th (1397).

Despite delaying the selection process for another two months. The interview with Mr Robert Etzenberger was held on the 16th of April 1872.

The services of Mr Etzenberger were secured then, after it was agreed that the hotel would be completed to Scott's designs.

Mr Etzenberger came in while the building work was still underway and made many changes of his own to the layout of the rooms.

George Gilbert Scott was knighted in 1872 for his work including the Albert Memorial.

Mr Sang's estimates that were accepted are shown as First floor £3750 (first scheme); Second floor £2,450 (first scheme); Third floor £1260 (first scheme); Fourth floor £600 (third scheme) and Fifth floor £460 (third scheme).

To facilitate an early opening, temporary public rooms would have to occupy the first floor of the South building.

A payment to Mr Sang of £3000 was shown in the minutes of April the 23rd 1873.

This work was carried out and the hotel opened for business on Monday the 5th of May 1873.

There was no ceremony or fanfare – it just simply opened its doors and got on with it.

This was probably because it was nowhere near finished – at the beginning of June Mr Skidmore was pressed to complete his contract and Jackson & Shaw were asked to put all strength into completing the kitchens, laundry, billiard room, smoke room and kitchen lifts.

Sir George was asked to 'put down wooden pavements under both archways' (min1499)

On June the 3rd it was decided to order ten pianos from Messrs Erards for the best Sitting-rooms; one grand, four oblique and five upright, all in walnut cases.

In July Sir William Armstrong was asked to supply a passenger lift and luggage lift for the Western wing.

The cost of these was £710 and £340 respectively. John Oldrid Scott obtained a scheme for extending the central heating to the West wing from Messrs Haden & Son of Trowbridge and this was given the go-ahead.

In September Mr Etzenberger requested early occupation of the billiard and smoking rooms but was told it would be two or three months before they would be handed over.

But there were other casualties of the savings craved by the Directors. They had returned designs for decoration of the West wing to Scott and his decorator, Friederick Sang.

When Scott realised that he was about to lose that part of the contract, he had another of his preferred companies, Clayton and Bell, send in some designs at a more favourable cost, but to no avail.

Finally, in November 1873 Sir George was told of the decision to remove from his control the decoration of the Western wing.

This would now be carried out by the furnishers, Gillows, under their own instructions.

Scott had retained the services of Francis Skidmore of Coventry to design and supply decorative wrought and cast ironwork to the hotel including the gasoliers.

Skidmore was a true artist and would often spend time on a design only to destroy the finished article when he found it not meeting his exacting standards.

The design, manufacture and fitting of these items, including the gas lighting, was so slow that it forced the Midland Railway Board to look carefully at the agreement that they had made with Skidmore and determined that there was no agreement for fitting them, so they informed Skidmore that engineers from the Midland Railway would carry out the fitting.

This speeded up the manufacture and supply and Skidmore was to get ahead of schedule enough to have to request storage facilities on the hotel site.

This was granted, but in finalising their account with Skidmore, the Midland railway board instructed that deductions were to be made for this storage and also for the gas used for lighting their work on site.

The Midland Railway Company were very concerned about the possibility of a fire in their new hotel and secured the services of Superintendent Medcalf of the Derby Fire brigade to come to the Grand hotel and survey the building to make recommendations as to what measures might be taken to lessen the effect of any fires within the building.

Work continued until the end of 1876 but the building was handed over to the Way and Works committee in July 1876.

In January 1877 Edward William Godwin invoiced the MRC for some designs for the vaulted ceiling of the grand staircase.

There are eight figures of the virtues, Humility, Industry, Liberality, Chastity, Temperance, Truth, Charity & Patience; There is also a ninth panel of the Midland Railway Armorial shield, depicting some of the cities served by the Midland Railway – Birmingham; Derby; Bristol; Leicester; Lincoln and Leeds and a medallion design which was used under each panel. Godwin had adapted unused drawings first created for the dining room in Dromore Castle, County Limerick, which he had designed for the Earl of Limerick.

The designs were applied to the ceiling by a man called Donaldson, of Gillows.

It is possible that this was Andrew Benjamin Donaldson, an artist of merit, as he is known to have worked for Gillows and there was some artistic knowledge needed to complete the entire ceiling scheme.

Many new ideas were used in the Midland Grand. The building was provided with the two 'Hydraulic Ascending Rooms' or lifts, as we would normally call them.

The first of these was fitted in the main east-west corridor, next to the principle staircase and the guest entrance from the station.

The lift operated on the 'jigger principal' and in its original form was quite dangerous, the hydraulics being so weak as to allow the carriage to 'creep' slowly down on being stopped, thus causing passengers to trip up the threshold when leaving, so much so that the MRC were forced to insist that Armstrong modify both the lifting principle and bring in safety measures.

Gates were fitted to the openings of the lift shafts. The seals used in the Jigger rams were replaced. An accumulator was brought in to increase the pressure.

In the mid-1880s a new concept was used. The Jigger system was replaced with a massive piston sunk into the ground beneath the lift carriage.

This piston was powered from the London Hydraulic Water Company system.

This second form of hydraulic power was so successful that the lift stayed driven that way until the late 1950s when it was replaced with a modern electrically powered carriage.

I have been lucky enough to meet ex LMS and British Rail employees that had travelled in the water-driven lift, and their general opinion was that it was very smooth and quiet, unless the driver didn't like you- he was able to cause sudden stops and starts!

The second hydraulic ascending room was installed next to the grand staircase. At first, the MRC decided that this lift would only travel to the fourth floor, but a new gable was built to accommodate it to the fifth floor, before the lift was installed.

This lift was rectangular and sat back in the shaft with a landing in front of it.

Behind both of these original lifts were rope-driven luggage lifts. To afford daylight into these lifts, there were roof-lanterns; fixed glazing that matched the windows of the building follow the line of the goods lift shafts to the exterior of the building; plain glass panels allowed this light to pass through the separating wall and into the passenger lift shaft.

Gas lamps, set in a channel at the front of each shaft allowed them to have light outside of daylight hours.

Another very modern idea was the inclusion of electric bells supplied by W.S.Adam. Bedrooms, Sitting rooms and Public rooms had a pushbutton next to the fireplace.

When pressed, a bell would ring in the main service room, which was at the junction of the West wing and the East corridor opposite the Grand staircase.

A Chambermaid would then attend the room signalling, to respond to the guest and fill their requirements.

The service room on each floor could provide everything needed by utilising two large rope-driven lifts and a dumb-waiter.

Stocks of linen, candles and coal were kept here. There was a tube down which orders for food could be dropped to the basement kitchens.

Speaking-tubes ran in all directions. A chute was in the corner of the room down which cinders could be deposited.

Another chute was provided for soiled linen to be dropped to the ground floor level, where it could be taken to the laundry at the North end of the West wing.

A large sink was provided with hot as well as cold water.

Hip baths were stored here, being filled upon request and wheeled to the guest room.

The hot running water was provided to service rooms throughout the building, supplied from a boiler in the basement with a steam engine to pump it around.

There was one attended bathroom on each of the accommodation floors (1-5) in the east wing of the building.

Each bathroom contained two large cast-iron, roll-topped baths, separated by a dividing wall and doors to each division.

Fresh towels, bathing oils and other bathroom requisites were kept in attendant's rooms and a chute was provide to drop used linen down to ground level, where they could be transported to probably the most modern hotel laundry in the world.

Equipped with the most modern steam-driven machines, including a six foot (1.83m) washing machine, capable of handling up to three thousand pieces of linen per day, drying cabinets and steam presses.

The laundry equipment was supplied by Clement Jeakes & Company of Great Russell Street.

Mr Saville, the Clerk of works announced the opening of the bridge at first-floor level between the two portions of the building.

Guest's servants could dine in the steward's dining room on the first floor at a more favourable cost.

If a member of staff were to be taken ill, they were not allowed to stay in the hotel for more than two days.

If they did not live locally they were to be removed to an infirmary.

There were two general types of staff; those that came from Europe and Scandinavia and they lived in.

Special terms were given to theatrical and operatic performers.

The staff for the new hotel were hired from all over Europe and the British Isles. The list of different posts is extensive:

There were also two distinctly different groups of staff, those that lived in, i.e. staff that had a dedicated room or bed in a room as part of their remuneration.

This applied to senior members of staff and also to those from outside London. A great number of staff not considered live-in also slept on the premises, mainly in attic rooms on the fifth floor. This was due to the lack of transport to fit in with their 70 hour working week, which was often also split-shifts.

It simply was not worth (or in many cases possible) going home to sleep. So they would sleep in building to save money. Many staff were also 'floating' between hotels owned by the Midland Railway.

If the Midland Grand Hotel was having a busy time, it could draw on staff from these other hotels.

A travel pass would be issued so that they might travel to St. Pancras, then when their need was no more; another pass was given to convey them back from whence they came.

The staff worked under very stiff conditions and rules, but in return there was a good rate of pay and a job for life, coupled with good benefits for those that made it their career.

Employees had a number of benefits available, such as privilege train tickets, the Midland Railway Friendly Society, etc

After due warning, fines were imposed on staff for breaking any rules.

These fines had to be agreed by the hotel manager before deductions were made from wages.

Any such punishments were also registered on the staff member's pedigree papers.

A tell-tale clock was used to police entry to the larder at night.

There was a great deal of regulation in clothing back in those Victorian days, not only for staff but also dress codes for guests – the less well-off guests, such as travelling salesmen, clergy, army officers and the like would either not be able to dress for the smartest of public rooms or not be capable of affording to use them.

In 1875 the least expensive room in the hotel was on the fifth floor at the back of the building, above the Barlow shed. It cost 3/6d (17.5p) per night.

Gillows, as was the norm in those days, referred to staff members solely by their surname, which makes positive identification impossible in many cases, especially where several generations were involved.

In a letter read at a meeting of the Southern Construction Committee on the 31st of March 1874 from Messrs Gillows, a donation was sought 'for the widow of Eldridge, in their employ, who was accidentally killed through falling down the shaft of the lift at the hotel.......'

Needless to say, the thought of paying compensation for something as common as death was reprehensible to the Board of Directors, as well as being an admission of liability and the suggestion was 'declined in consequence of the precedent it would set up' (min 1673).

The last man recorded as dying in this lift shaft is Charles Kyne. Mr Kyne was working as a fire watcher in the building on the 30th of December 1940.

It was his turn to go up to the roof to carry out his responsibilities, and as with the others carrying out such tasks around the building, he was to use the water-driven lift to take him to the fifth floor – there was no driver – so the staff would look up and down the shaft to see where the carriage was and then lean into the shaft to pull the control rope that would bring the carriage to them.

On this occasion Mr Kyne failed to move out of the way soon enough and was struck on the head by the moving carriage, which fractured his skull. He was taken to the Royal Free Hospital by ambulance, but died shortly afterwards.

Table d'hôte cuisine in the Coffee Lounge was 5/- (25p) which was more acceptable to those spending considerably more money on the suites on the first to third floors.

The hierarchy of the letting rooms was such that the most expensive were on the first floor, the least expensive on the top floor.

Each floor had a different quality of furniture and fittings.

The higher the ceiling height, the more expensive the room was. The first floor is approximately 18 feet (5.5m) high.

Each guest room had an enamel plate to denote the room number, blue numerals on a white background with a thin gold border.

The rooms all have balconies accessed through very tall French windows fitted with the highest quality brass espagnolets and other brass furniture.

The fireplaces on this level were made of marble. Any number of rooms could be made into a suite by utilising adjoining doors within the rooms.

The furniture for the best guest rooms was made of Walnut and black wood inlaid with gold. In the sitting rooms it was made of Fine walnut with gilding.

Mirrors above the fireplaces in these rooms measured................... Curtains were made of Silk damask lined with merino.

The fire irons, Coal buckets, ornamental vases, washstands commodes and chamber pots were all of the highest quality.

On the second floor, the ceiling height reduced by 2' (60cm) to approximately 16' (4.9m).

Here too, the rooms on the front elevation had balconies accessed by French windows. Again the rooms could be made into suites by using the interconnecting doors.

The door furniture for guest rooms was of a lesser design than that used on the first floor. The fireplaces on this floor were made of York stone.

Smaller than those on the first floor, yet still relevant to the size of room they occupied, each was topped with a 'marbleised' mantelpiece.

Furniture for the sitting rooms on this floor was made of Fine walnut with gilding.

The bedroom furniture was made of Teak or Oak. Curtains were of silkwood tapestry.

The east end of the second floor was reserved for the use of the Midland Railway Board. Here there is additional stone carved decoration at height in the corridor as if to mark-out the start of the management territory.

There were meeting rooms and guest rooms and at the South-Eastern corner was the board room, a double-aspect room looking down on the great rivals the Great Northern Railway at St. Pancras.

Interestingly, this was the only room to be fitted with early secondary glazing, and only on the Eastern side of the room, the side overlooking the Great Northern Station.

The ceiling of this room had a splendid geometric pattern painted directly onto it and designed by Friederick Sang/George Gilbert Scott.

The balconies continued into Pancras Road.

In the West Chamber on this floor a late decision was made to insert a so-called 'Turkish bath'. An iron tank was suspended through the floor of the room above the mezzanine service-room, overlooking Midland Road.

Into this tank was built a ceramic-tiled bath, with steps going down into it. The cream yellow tiles had a band of gold leaf around the edge.

A handrail was fitted for safety and the wall running parallel was also fitted with a mirror and a surround of tiles to match.

An extraction duct was fitted through the ceiling above the bath.

At a committee meeting on the 30th of June 1874 a tender was produced and accepted from W.S.Adams 'to provide and fit up one electric communicator from the Turkish bath to the Steam boiler house.(1724).

There were also balconies on this second floor in Midland Road near the junction with Euston road. These balconies are now gone, as is the 'Turkish bath'.

On the third floor the ceiling height once again reduced by approximately 2ft (60cm) to be about 14ft (4.25m) high.

The rooms are the same area as those on the second floor. The door furniture is plainer, the bedroom furniture made of Mahogany, Sitting room furniture of Walnut & Blackwood.

Smaller sash windows make the rooms darker, yet the proportions here seem better – the rooms appear bigger.

The fourth floor ceiling height comes down to approximately 10ft (3m). This drop of 4ft (1.2m) is because the original fourth floor was removed from the building plans entirely, and this level is now within the roof

The door furniture was yet plainer still than that on the third floor, the doors were smaller and plainer, having only four panels.

The furniture was made of Ash. The curtains were wool damask.

The fifth floor room ceilings were approximately 8ft (2.4m) high. The space above these rooms was used for storage and for staff to bed-down in.

The overall height of the fifth floor corridor is approximately 20ft (6m). This corridor has roof lantern (skylights) that are designed at an angle to suit the trajectory of the sun.

The two staircases in the east wing also have roof lanterns to light the stairwells.

The furniture was made of Ash in the guest rooms and Deal 'japanned' as oak elsewhere. There were servant's bedrooms over the Grand stair vaulted ceiling.

The Terrace Entrance was the first entrance to open, taking place on May the 5th 1873. A glazed cast-iron framed canopy, supported by four cast-iron posts, stood on the terrace outside. When entering here in 1873, as well as reception facilities there was a waiting room, a day room, a refreshment room and a bedroom suite. A corresponding entrance, slightly to the left of this one, was present in the station, and thus, passengers were able to enter the building here without an unnecessary walk around the outside of the terminus.

The first of the two passenger lifts was present here, in a shaft with openings on both North and South aspects, allowing entry to the carriage through a sliding gate.

A driver was provided for the safe operation of this new invention.

On all other levels the egress was only on the South side. Next to this lift on the west side on each of the floors from first to fifth was a luggage and service room provided with a luggage lift to the rear (North) side of the passenger lift.

The goods lift was at first designed to carry 8cwt (400kg), but on acceptance of the tender the board asked that it be increased to 10cwt (500kgs).

The goods lift was rope driven. The room was also provided with a double ‘Butler- style’ sink with a bucket stand and flushing mechanism on one side.

To the right-hand side (East) of the passenger lift is a magnificent spiral staircase referred to as the ‘Directors Staircase’ in some drawings.

This leads only to the first floor corridor and the early public rooms.

Because the West wing was still under construction in 1873 and the finished rooms were still to be decorated, a number of temporary public rooms were created at first floor level, only used until the corresponding rooms were ready in the West wing.

Among these was a stunning pair of rooms on the south side of the East corridor separated by cast-iron columns topped with carved stone arches, decorated with wrought ironwork.

Each room has an identical marble fireplace and stunning geometric ceiling painting.

They were used as a temporary coffee lounge. Once the permanent Coffee lounge was established in the South of the West wing at platform level, these rooms were separated by filling-in the archways and bricking up the openings to form two separate bedrooms.

American traveller, Moncure D. Conway wrote in his ‘Travels in South Kensington’ (New York 1882): ‘The halls and corridors have a dado of fine dark-brown tiles, and bright fleur-de-lis paper above.’ In 1899 the hotel purchased two revolving doors from the Van Kannel revolving door company of Philadelphia.

Fourteen year old Reginald Squires started at the hotel in 1912 as a page boy on 3/6d per week (17.5p).

On the 31st of December 1922 the Midland Railway became part of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway under the government ‘Big four’ grouping policy.

This saw the Midland Railway join up with the London and North Western Railway and the Caledonian Railway.

The hotel closed on Friday the 19th April 1935. Reginald Squires was by this time, the head porter. He was retained for two further years after the closure, along with a colleague, Stan Humphrey, to wait in the station for potential hotel guests and to take any down to the Euston hotel rather than they should venture outside and happen upon the Great Northern Hotel – the rivalry remained! The Head Page boy was Ronald Regan.

He only started in 1934 and was paid the princely sum of 7/6d per week, with free rail travel from his home in South Tottenham.

When completing split shifts – 7am to 2pm then 5pm to 10pm, Ronald would sleep in one of the rooms on the fifth floor.

Other members of staff at this time were: Mrs Bailey, the Head Housekeeper; Mrs Fowler, the assistant Housekeeper; Mr Dane, the assistant manager; Mr Gurney, the manager; and Arthur Towle, the Controller.

Famous guests included Jesse Boot (Boots Chemists), George Pullman, Mr Pilkington; Lord Leverhulme, Derby County F.C; and an intriguing character called Charlie Hannam.

Mr Hannam always stayed in room 104 and was a professional gambler.

For additional information on the areas we cover and the range of services we provide please contact us or call us on 01843 290141 | 07778 932359.